Geeta Chandran masterfully retells Simhika myth for social message

Bharatanatyam guru Geeta Chandran gave a solo performance at the IIC in Delhi in December last year called ‘Simhika: Daughter of the Forest’. The research and creation of the production was supported by a Special Project Fellowship to Geeta ji from WISCOMP (Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace.

The protagonist of the tale, Simhika, is a fictional character created for Kathakali play ‘Kirmira Vadham’ written by Kottayam Thampuran. The script has been adapted from the play by Geeta ji and translated into Sanskrit by A.R. Sreekrishnan.

Simhika is a demoness living in the forest. The forest is not only her friend, sakhi (friend), confidant, sakshi (witness) and nurturer, but also her betrayer. It is also a mute spectator to injustice and patriarchy. Geeta Chandran has enacted the solo as the protagonist, Simhika, and the character has been revealed using anavarnam, or unveiling layer by layer. There is also the transformation or roopantar of the character.

According to the mythological tale, Simhika was a forest maiden who lived in the Treta yuga during the period of Mahabharata. She lived peacefully in the forest with her husband in perfect harmony with nature. But her perfect life came to a tragic end when her husband Shardul was brutally murdered by the Pandavas. A broken and pained Simhika seeks to take revenge. On the outside, she becomes a beautiful maiden and plans to befriend Draupadi and kill her. But alas, she is betrayed by her soulmate, the forest, and Sahadev, Draupadi’s husband, defiles her body by chopping off her breasts. Simhika ends up losing everything – her husband and her best friend, the forest – and with her mind and body both mutilated.

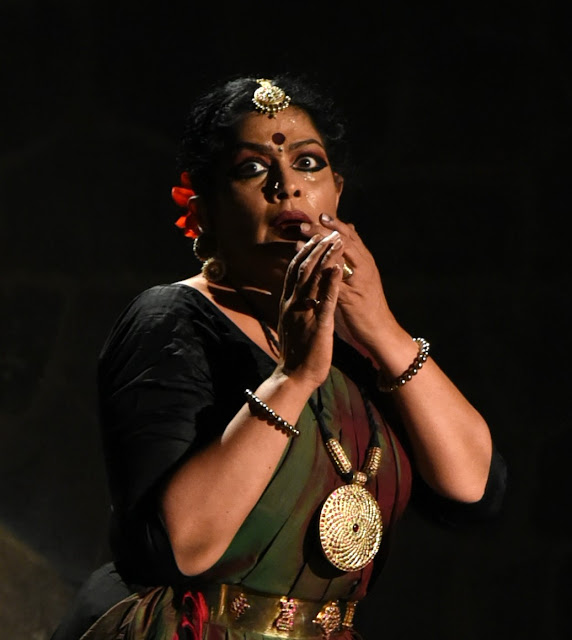

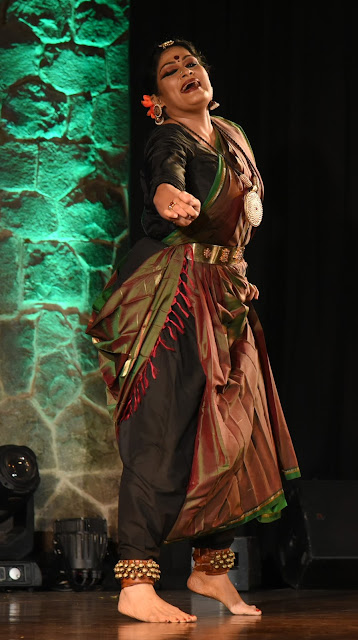

The Mahabharata has a few such stories from the exile of the Pandavas which are similar, but Geeta ji gave the story an artistic interpretation as well as an environmental message. She was dressed in a brown and green costume by Sandhya Raman, which matched the colours of the forest, and was accessorized mostly in black.

The original set for the production had been made out of pattals (dry leaf plates) and crafted by Jugal Kishore Sharma and his team of traditional flower decorators from Vrindavan. For this staging, the back wall of the IIC stage looked like grey boulders, and with green light falling on it, it gave the impression of a forest. Some pattals were scattered on the stage, giving a sense of fallen leaves. The ambience was that of a forest.

In the first scene, Geeta ji sat on the stage, rubbing her hands in great pain and anguish as her body has been defiled and her husband has been murdered.

And then she reminisces about the time she had spent in the forest living peacefully with her husband. She remembers that when she was a baby, she had been put in the river by her mother in the forest. The forest nurtured her like a mother and also became her close friend. She would hug the trees and play around them, and it was pure bliss. She would play kikli with the trees. She would adorn herself with the flowers growing on the creepers and their scent would fill her. And while Geeta ji depicted this in abhinaya, there was vachik abhinaya too – ‘ae vana mata sakha jeevita sahachara’ was repeated for this scene.

The daughter of the forest has wild animals as her friends. She caresses the trunk of the elephant and feeds branches to it. In turn, it showers her with water from its trunk. She plays and frolics with the deer and feeds fresh leaves to it. She loves its beautiful eyes. She listens to the songs of the birds and dances and claps to them. They are like yugal or twins – she reflects the forest and the forest reflects her. She is firm like the tree, which stands its ground in the storm. Her breasts are like the flowers. She is like the sun, which gives light and warmth. As she plays in the stream of water, she matches her gait to its path.

In the next scene, she has tidied up her hut. Geeta ji showed Simhika rearranging the pattal on stage, scattering flowers, lighting the lamp and waiting for her husband.

Suddenly, there is a knock on the door. She is shocked to see her husband dead. To her anguish, he has been murdered and his body chopped by the Pandavas. The brutality was enhanced by the rhythm of the ghatam and mridangam.

When her grief peaks, it is transformed into anger and vengeance, which forms the basis of the roopantar of the character. She turns from an uncouth forest maiden into a beautiful woman. Here, the story was enhanced by the lighting. Geeta ji’s shadow was cast on the wall to show the change. Standing in broad plie, she ties her tangled hair into a bun. She rubs her hands on her face, which then becomes like a full moon. Her eyes and lips become like lotuses. Her breasts become rounder like a kalash and her waist smaller. She wears shiny clothes rather than the ones made from the bark of trees. Her rustic ornaments made from plants are replaced by jewellery - bangles, nose pin, payal (anklets) etc., and there is constant chanting of the word ‘chhal’ (deception). Very forceful percussion and footwork were used to enhance the effect. Simhika, as her alter ego, is like a golden pot filled with poison.

She goes to befriend Draupadi and takes her into the forest to avenge her husband’s death. But alas, it is her friend the forest who betrays her. The flowers start smelling foul, the doe-eyed deer retreats on touch, the birds cease to sing as they are approached. The bees cease to hum over the lotuses. Draupadi senses the danger to her life and she begs Simhika for her life. In the meantime, Sahadev, her husband, who comes looking for her, rescues her. He not only defaces Simhika but also chops off her breasts.

Geeta ji depicted this by wearing a red and orange cloth on her face and body and the red light glowing on her. The injured Simhika, bodily defiled, ego hurt and emotions shattered, is totally broken because of the betrayal of her friend the forest. She falls to the ground clutching her chest in pain. The red lights and Geeta ji’s expressions enhance the expression of Simhika’s pain. Geeta ji’s skill is the Midas touch, which transformed a minor character in a regular mythological story into an enthralling performance with a social message.

|

| (L-R) Sharanya Chandran, K. Venkateshwaran, Manohar Balatchandirane, Geeta Chandran, Varun Rajasekharan and G. Raghavendra Prasath |

Here, to assist her storytelling, the rhythm and music created a forceful impact, especially with Manohar Balatchandirane on the pakhawaj and the beats from the ghatam by Varun Rajasekharan. The music scape for Simhika was developed by Geeta ji, vocalist K. Venkateshwaran and Manohar. Sharanya Chandran was on nattuvangam and G. Raghavendra Prasath was on violin for this staging.

There were the lights and then there was the backdrop, which was very appropriate. At one point, the sound of claps was used to enhance the rhythm. The costume always is very appropriate in Geeta ji’s performances and her command over the abhinaya, her evocative expressions and her mastery over her craft always give her an edge in her depictions. The lighting by Milind Shrivastav complemented the stage setting by the use of shadows. The social message, as Geeta ji put it later, was how man has defaced and defiled the forests.

--

What Geeta ji says

The concept came from a very small character in a Kathakali play, the Kirmira Vadham. The main character is Simhika’s brother Kirmira. She’s a very small character but I found it interesting because I could build on it and because she’s a fictitious character. In today’s day and age, you take any character and you do something, people are up in arms – how could you do this and how could you do that. So I thought, this is a fictitious character, no one can say anything about this! I can say what I want to say.

I watched a lot of Kathakali (to prepare for Simhika) but in those productions, Simhika is black and white. Black is when she’s a rakshasi – she’s shown like that, the aharya is terrible. And then when she does the roopantaran, when she’s a beautiful damsel, another person performs the character. There was no grey in the middle – that’s black and ugly and this is beautiful. But when I read it again and again, I thought this has possibilities to see what the storyline is doing to her.

The forest is theirs. We have gone into the forest. The Pandavas were exiled; they went into the forest and they intervened in their lifestyle. They are threatened by this rakshasa, her husband, and they just kill him without any tangible reason. There is no reason given. It is the Pandavas who are going in and killing him, and then she is widowed. And then, instead of killing her, she is defaced. He could have killed her, but he wanted her to be defaced and dehumanized and suffer. Where does it say that you have to do that to women? Surpanaka is the same – defaced, never killed. I just thought of this whole thing about patriarchy and how they like to put women in their place by defacing them.

There were so many messages in this. As I went on working on this, I realized that the forest has been her partner in everything – bachpan se wahin pali badhi hai, like a sakhi – and then the same forest gives her away, just like in society, some people are very nice to you and then you see the same people letting you down. And then the same way, people are judged by what they look like. If they are beautiful, people want to flock to them. But if they are not, then they are judged as being unimportant. Or based on their clothes, the outward appearance, they are judged as not worth investing in. So many things came to me that could be taken up. People take back whatever they want to from this. I had so much I wanted to say.

Of course in the Kathakali, there is no such thing as the forest ‘deceiving’ her. They do depict, of course, how in the end, the forest does give signs to Panchali that there’s something amiss. There the forest does give her away, but they don’t say it that way. But in my production, the flowers lose their scent, the deer is wary, the bees come away from the lotus and buzz in her ears. This is not in the original poetry.

But what I took from Kathakali was the pace – the slow vilambit pace, because their Kathakali padams are all very slow. In the roopantaram and in the vanadarshan, I took something resembling that slow pace and I wrote the whole script in English. Then I gave it to the Sanskrit scholar and it took me one month of back and forth (to finalize the script). But he was very good, he understood that I had to sing it. So I would sing it and if it didn’t work, I would send it back and he would change it . . . We did back and forth because he was in Trivandrum. Also, there were many lines in the original script. Phir maine usko kaafi kaat diya, I kept it to abhinaya only. I didn’t want it to become wordy. I wanted the whole thing to come out as a docu-drama. We did a lot of work on the music.

The premiere of Simhika was in Kalamandalam and it was very well-received there. The Chakyars received it very well, though some traditional Kathakali artists found it very different and they couldn’t relate. They are used to that character being done in a certain way for so many generations, so the contemporization . . . But many of the Koodiyatam people loved it. A lot of them came and told me later it was very beautiful. And they had scholars, musicians, thinkers in that session, so it was nice to get feedback from them.

I think society is ready for these kinds of things, it’s just that we are moving to spectacle – many bodies, noise, etc. I feel the quiet, the subtle, the nuance is being lost. And what is the message? At the end of the day, the arts have a social responsibility. Are we just entertainers? Circus people are also entertainers. Are we in the same genre? Don’t we want to make people think, make people cry, don’t we want people to take something back and think about it? For example (after watching Simhika), five of my students said Akka, I can’t speak anything, I’ll write and send it to you. That’s it! All night they’re going to be sitting and thinking about it, and then tomorrow morning I’ll get little pieces from them. Art should make people think, make people ponder, make people emotional. Just entertaining . . . Somewhere, we ourselves have marginalized the role of the arts, what art can do. We are taking it towards entertainment. I feel this space needs to be kept alive.

Comments

Post a Comment