Rango'ntaratma: An interactive session

Artworks by Himanshu Srivastava

As you entered Kamani Auditorium for the performance, what caught your eye first was the display in the foyer by Himanshu Srivastava, a Bharatanatyam dancer who is also an artist. From the left, there was a lotus lamp in a flower rangoli, a ceremonial lamp, green strands of leaves with a damru attached to them, a bell, a metal urn on top with flowers coming out, mridangam, pakhawaj, a face mask, harmonium, a clay ghatam (pot) with sticks of rajnigandha, a blue face mask, tabla, a stringed instrument, a manjira, a black mask and then a huge metal urn from which ghungroos hung out, saris, an urn with flutes, a smaller stringed instrument, a South Indian dancing doll, conches, drums with sticks, khartal etc. Himanshu said, "I avoid watching rehearsals so that I do not get influenced. I simply get inspired by the theme. I had been given these 20-25 instruments to make a display and the moment I saw them in front of me, I thought there was harmony in that chaos. The saris I used because I like to play with fabric." There was a huge instrument shaped like a semi-circle with small flags attached to it on the extreme right.

It was a preview of what was to be seen on stage, a fusion of many elements to show the origin of art. The huge ghatam, which was the centerpiece, was to show the void of space through which the first emanations of naad happened. In the medley of the instruments, there was the thread of music that creates harmony, stringing them together.

|

| Paintings by Himanshu Shrivastava |

|

| Kamalini Dutt |

KAMALINI DUTT

Arshiya Sethi: We had all these old textual references in the production, and then we had all these modern poets like Nirala and Subramania Bharati.

KD: Even the old texts were not so old; Muthuswami Dikshitar is only about 200 years old and the same with Thyagaraja. And Abhinavagupta is 6th-7th century. To me, there is a continuous thought process which is more important. Whenever we are doing something classical, we must keep some modern sensibility. Suryakant Tripathi and Subramania Bharati have been with me for almost 40 years. When I heard it in college, I thought what a wonderful composition is this - 'tum tung-himalay-shring, aur main chanchal-gati sur-sarita'. What a beautiful compatibility of a man and a woman! That's how it should be. It is not about who is stronger. It is about the dance and the inner dancer.

Man or woman, the guru is genderless. The other is imaginary; we imagine the other so we can fight. The woman is not an other for the man and man is not an other for the woman. That's all a power game. Abhinavagupta says there are nine rasas. He says if you understand the emotion in the rasa, then you get the maharasa. Each time he keeps coming back to one, one, one. In Vaishnavism, there are two. And then he says, 'Tum tum nahin main main nahin' (You are not you and I am not I). These are the nuances of Hinduism. And bhakti did not start with Vaishnavism. Abhinavaguptacharya said, 'Brahma hai mujh mein leen' (Brahma is immersed within me). This was what he believed in.

AS: The images, the art by Santosh and other images, were used beautifully - how did you link them to the rest of the production in terms of what had to go where?

KD: In images, you have Shiva's hair standing up when he is listening to music, whoever is playing and whatever is being played. Even in Nataraja, you say that the hair is moving when the hands move. It is the height of ananda and the dance is ananda tandav. With Santosh, I have worked on a project on Nareshwari and he gave me this image of Shiva which is not shown anywhere else, it is only on my video. Interacting with these people, talking to them opened up so many nuances, and they just came and sat in on the production. I did not have to make an effort.

Leela Venkataraman: Did you deliberately use the 9-beat cycle in the Alarippu?

KD: Yes, it was my choice. It was a 9-beat cycle - nava. It is not a usual beat. It challenges you.

AS: Your choice of ragas stood out in this presentation…

KD: Those were cold, bitter nights that S. Vasudevan, Satish Venkatesh, Rakesh Pathak and I spent making the music. I was in pain, utter pain, when suddenly we saw it was Bindumalini, Amritavarshini, it was devi. Everything just happened and it was at a different level. On 26 January, the coldest day, when I entered the womb of the recording studio, it was like reverse osmosis. Ten days before, it was all tranquil. Chitaranjini to Bindumalini, I was given the ragas. Creative inputs came from all angles. Well-known tabla exponent Govind Chakraborty was amazing. He gave the padhant and contributed significantly to the rhythm structure for the Kathak music in Rango'ntaratma. In Kathak, if the padhant is not done the proper way, it loses its power.

Why were the mantras and name of Kashmir Shaivism, Trika, not used in the music?

KD: Oham-soham is ajapa. It was given to us by our guru and it has to be only meditated upon. I did not use technical terms like Trika because the production was not Kashmir Shaivism. It was ranga inspired by Kashmir Shaivism. It was Abhinavagupta's idea of ranga or a performance. When it comes to naad, bindu, kala, these are all mentioned but when it comes to Vigyan Bhairav, all these things are lower level. You have to rise above all this. Naad, bindu, spanda are all expressions and you have to go beyond what has been manifest. Shiva tells Parvati beautifully that all this is done but we have to go beyond this.

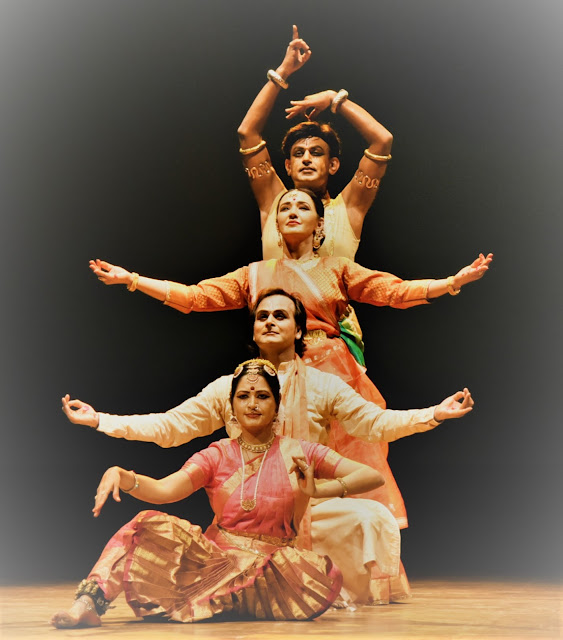

PURVADHANASHREE

Purva did the first Bharatanatyam solo which invoked Shiva as the naad tanum, with five faces. She learnt Bharatanatyam from her mother Kamalini Dutt and Vilasini Natyam from Guru Swapnasundari.

|

| Purvadhanashree |

Alarippu is such a powerful piece that in whatever taalam you do it, the entire temple comes in front of you. As a dancer of the 21st century, it was a challenge to bring the temple in front of the audience because we are the temple. Alarippu is like monumentalizing a thought. It is not like moving your hand this side or that; I have to feel the temple inside, only then will it be outside. I have to be not joyous at that time. It is not just a nritta piece. I am very meditative at that time so that is the challenge for me. In 'Naada tanum…', those four beams of light were very effective and so was the sound. Since it was a piece about soundless sound, it was a challenge and I had to communicate the silence inside to the audience. I am looking for the sound; it's here, it's there, no, it is inside me. That took me to 'Ardhanareeshwara'. In today's time, in the gender dialogue, sometimes people do expect us to support one gender, and if we talk as women, then there is a problem. The ardhanareeshwar concept is powerful and timeless. The best way to experience ardhanari is to dance ardhanari, where you show the masculine and the feminine.

And Vasudevan's piece is… what can I say? I have a spiritual background because of my mother but to see the Yantra Kamal like that, it was frightening also because of the way Vasu did it. Sometimes it was scary in rehearsal. There's one point when he shivers, and that happens to a yogi. We had been hearing it but to see it in dance… It's a place that I can never reach, but that was an experience I would love to have again and again.

The last piece was very elevating from a human experience point of view, an experience that each man and each woman wants - to dialogue on equal terms, and we struggle with that in our personal spheres, where the partner is accepting you the way you are, dialoguing with you on equal terms and then deifying you. I'm not saying it gives ego, but to see god in the other is what we want in life… to do that in dance is beautiful.

We worked on this in the rehearsal, in this Tamil composition which describes the journey of a man and a woman in which they see each other as partners first and not deified. In the beginning, I tried to tell Vasu, 'I'm your partner, not a devi,' and he was finding it a little challenging. And that was the idea of one pair here and one pair there, and how those two relate at an earthly level and then how they see the god in each other. That was what we had to work on - to see each other in the love of us and not as god and devotee. We had that challenge in the beginning and worked on it under my mother's guidance.

DR. S. VASUDEVAN

|

| Dr. S Vasudevan |

All the four dancers tried their best to come up to the expectations of our mentor Kamalini Dutt. This was her brainchild. It was her dream project. She is very deeply into Shaivism, which is not separate from shakti upasana. We talk of Shiva-Shakti oneness. And I, being initiated into shrividya upasana, personally admire this philosophy of Rango'ntaratma. Kamalini Dutt, through her thought, research and practically living in this concept and dream shared her ideas and gave shape to this concept.

This is a very esoteric concept which has been mentioned in Shaivism, Shaktism and in Kashmir Shaivism through the verses of Abhinavagupta. Kashmir Shaivism is practiced in many parts of the country in many ways. We took verses from Thyagaraja, one of the Carnatic music trinity - Naada tanumanisham shankaram - which is very close to Kashmir Shaivism. When we speak of the deliverer, it takes us immediately to bindu, or the mother, who is the bearer of the entire universe. So Shakti delivers, produces and propagates the universe. Shakti takes us immediately to the big blast which manifests as a huge limitless universe. In that we live as specks, trying to live as human beings, trying to figure out the root of the arts. When we speak of the pure consciousness, it is related to the metaphysical world, not the physical world. 'Rango'ntaratma' - the very words come from Kashmir Shaivism, from the Vigyan Bhairav Tantra and Bhairav Tantra Stava. These are basically Abhinavagupta's terms.

I, as a dancer, was given bindu to depict. I did not know how to start with bindu. So I started with 'Kanakambari' in ragam Kanakambari, the first melakarta in the Carnatic tradition. In this composition, he very subtly depicts the navadhara. There is a lot more between these navadharas and shadachakras. Within these navadharas are the panchabhootas, within these somewhere are the pancha karmendriyas, pancha jnanendriyas, and many more things. So everything - the rasas, the naad, the kala, the kaalas - everything is born out of the bindu. It is the core or centre for everything. These compositions cannot be handled by Bharatanatyam alone. Bharatanatyam is a dance form, but this is a very yogic kind of work.

My initiation into shrividya upasana helped here. These mudras are very sacred and secret - unless one is initiated, one cannot practice and exercise these mudras and mantras. My knowledge of this upasana made it convenient for me to depict the devi and talk about her navadharas and bindu and the rahasyas around this concept, where she unites with the Shakashiva and where she becomes Shiva herself. She is the dominating energy and where she is not awakened, Shiva is shava or the nirguna parabrahma. The journey from nirgun to sagun is sashakti. So if the shakti is not there, he is not moving, he is not doing his panchakritya - srishti, sanhar, stithi, tirodhana, anugraha. This is what we saw in the naad concept shown by Purvadhanashree. These are the five forms of Shiva, the five attributes of creation, destruction, sustenance, protecting and holding them and anugraha, which is the ultimate state which is even above moksha.

In the Shiva Shakti upasana marg, each term is hyperlinked to the state of the upasaka, which are sanidhya, sameepya, sarupya and saujya. Saujya and anugraha are not the state of salvation but of enjoying oneness. Moksha is the state where the being is lost. Here, nothing is lost, as we claim that energies cannot be destroyed, which is also a scientific fact. The energy keeps on changing, keeps on manifesting, keeps on processing itself; its dynamism is eternal and endless. That endless energy was focused in this composition 'Kanakambari' - like it says, 'dinkar chandra tej prakash kari', you are the burning sun, source of light, you are the cool moon, the source of nectar, the source of fire which burns and turns all to ash for rudra. The cycle of creating, sustaining and destroying is continuing but what is not changing is you, bindu. That one thing is constant and that one thing is svechha. She herself desires and designs the process of her lifecycle. Thus, only Shiva could desire and design her. What is not changing is you, the bindu. Shakti is approached only through Shiva. She is understood and channelized though Shiva. Otherwise, Shakti is very hard to understand. She is the superior and the supreme truth.

In Indian tradition, the worship of Shakti is undebatable. We cannot comprehend that energy. The male energy is the subordinate energy. This is the ancient truth, the law of nature, and we still live by it. People deal with it differently due to their Shakti and Shiva imbalances. But the truth is that to obey Shakti you have to be Shiva. And I have to mention Himanshu Srivastava who exclusively created these paintings which has never been thought of before. He heard these compositions, understood them word to word; he understood what Dikshitar's perspective of it was and what he was going to interpret, and then came out with this brilliant art piece.

Choreography of the piece

I tried to show the Shakti and the body of Shiva holding the powers of Shakti. Only Shiva is equipped to hold the powers of Shakti, I had tried to be the body of Shakti. Shiva, at times, is emotionless; emotions arise when Shakti enters him. He is naturally destructive. When Shakti inside him is resting, he destroys, it is pralaya. And when Shakti inside him is active, when she sees that all is darkness, she becomes the bindu, which expands into anything she desires - it could be light, a planet, a star, any colour, odour, any form, a hill, a river, any creature… but with an expiry date, again. That Shiva decides. She has created and Shiva destroys. Another concept for this is mithya. Adi Shankaracharya called it jagan mithya.

According to Advaitavadis, this world is fake. According to Shaktimarg, it is not. It is true because it is changing. Change is the proof. The existence of the constant is proven because of change. Once you start having the same food every day, you will become Shiva since you will lose the rasa. If you repeat the same activity over time, it is shavatvam since there is no variety. Variety is created by Shakti so that Shiva is engaged in sagunatmikta and not nirgunatmikta. Each syllable in the Shiva Stotra stands for each of his activities. From destruction to eternity, the journey is controlled by Shakti. For Shiva to have rasa as Kameshwara, she has to come as Kameshwari. The same body

DIVYA GOSWAMI

Divya, in her graceful Kathak, did a solo showing the attributes of the Devi. Divya hails from the families of Hindu philosopher Swami Ram Tirtha and shayar Pt. Kirpa Ram Sharma 'Nazim'. She was initiated into the Lucknow gharana of Kathak under Guru Yogini Gandhi at Pune, where she learnt for over 15 years. She is presently training under Guru Munna Shukla.

|

| Divya Goswami |

Kathak has seen this transformation where we see that the classical dance has only a few bandishes in this manner. In Kathak, we usually use tishra. Now these things are neither used nor taught. Kamaliniji liked the idea and thought it was going to be more challenging for everybody. Govind Chakraborty and my guru came to my rescue. Govindji helped me extensively in finding compositions with 5, 7 and 9 patterns, since they are rare combinations now.

Preparation wise, it took me a very long time. I had to find the correct bols for the correct composition. You cannot use just any bol you feel like - it has to have some significance. Based on that, the way the structures are available to us, Govindji gave me some compositions. My biggest challenge was that segment because we have never done anything like that. And laya is very close to my heart. It might be very difficult when I practice and it might take me two months to get there, but when I'm on stage, I dance only those compositions which I can dance with ease and people can appreciate for the beauty of the composition, not its complexity. So I had to reach that stage. At that time, Govindji said a very beautiful thing to me because I was finding it very difficult. He said, "Don't run behind the laya. Just let the laya and the structure of the jaati come to you, so you feel the chhand and the chhand will speak to you." That is how I started approaching the compositions thereafter and I choreographed the movements also in that fashion. Guruji then watched the movements and made his suggestions. That is how eventually they both let me be with the compositions and choose from the variety.

This was one aspect. Before me, there was an hour of Bharatanatyam and the Bharatanatyam approach to the whole concept was very different from Kathak. So I had the challenge of coming right after and doing what everybody does in Kathak, which is taal. I did not want to come on the stage just doing taal. Each style has its own beauty, Kathak's is in its taal, and we have to appreciate our style for that. Kamaliniji came up with this wonderful idea that we could use the name of the devi with the number of the jaati that we are using. For instance, with three, we used trista, trayee, trivarganilaya, tripuramalini - everything that begins with three. That gave me ample scope to bring the concept of the devi into the fold of Kathak and then the same concept in a couple of compositions I tried to portray in the bols as well, where I did not do the typical movement but how the devi looks in my imagination when I'm talking about three. Couple of places, not everywhere, because I wanted to retain the abstract nature of Kathak also. I tried to strike a balance and this is how the structure of my first part of dance evolved.

The second part was the devi's coming into play. Till now, the devi was just being imagined by Purvadhanashree in the forms of sound and she was being invited into the foray of the space we were all creating by Vasu. My part was the first representation of the devi being there dancing. Kamaliniji thought of bringing it with the concept that the devi and the devta, the male and the female, are just two opposite energies. So when we say this is Shiva and this is Parvati and this is Radha and this is Krishna, what we mean is that the energies are going to be in a leela, in play. Kamaliniji thought that the best way to show that interaction from the point of view of the devi, would be to use the 51st shloka of the Saundarya Lahiri, which is 'Shive shringarardra'. The shloka describes the nine rasas that Shiva and Parvati feel for each other, in just four lines of Sanskrit. The shloka was about 15 minutes, but we had to truncate to about six or seven minutes because the scope for me to expand it in the forms of sancharis was very limited in this production. You come from an abstract sound and abstract presence to the form, and then again you move back into the abstract. This was the cycle we wanted to depict. That is how my section moved from depicting a form or a special structure, very limited interaction between two energies, and then moving on to the abstract.

What do you think about ascribing a shape to the taal, like what Manohar Balatchandirane did?

Around the last 20-25 days, Kamaliniji had started developing the video part of it and though it was not final, she showed it to me from the start, what the structure is and what I have to do. I sat down and thought about what the structure means to me. I think structure is about three things - repetition, pattern and design. For me, repetition is, e.g., tishra, it is the chhand. For me, the maatra has to stop and some repetition of the tishra has to start taking over. From this repetition I create a pattern, a structure with the use of our sounds, our bols, which is the most beautiful thing of Kathak. Unfortunately, we were not able to recite the bols live while performing. We had the wonderful voice of Govindji doing the padhant. From that I designed the pattern, and what came in front of me was a structure in the form of a triangle, with the shape, movements and sam. This is how I treated all my jaatis - what is the repetition, what is the pattern, and finally, how am I designing it in my space by giving it movement.

What was your experience after performing it - did you find any change in your inner ranga?

While I was preparing for it in our rehearsal, I would be watching Bharatanatyam for the first hour during our rehearsals - it is very natural for you to get influenced by what you are seeing. It was very rightly pointed out by Hemant and Vasu to me that you should watch and not be influenced. I thought I was not doing it but then I watched a video of me and realized, my God, how much it is influencing my psyche. I had to watch and just be a witness to what was happening with the dancers before me, with such a strong concept and music before me. In my rehearsals, I witnessed it in all its beauty and did not let it influence me at all.

On the day of the show, before the show, I was so nervous- when Vasu was dancing I was backstage, I had to go down to the green room, breathe, close my eyes and sit for a couple of minutes. I only came up when there were a couple of minutes to go, and finally, when the Kathak commentary started, something took over, something magical happened to me, but I guess it was the preparation of so many months with Kamaliniji and such wonderful artists. And you won't believe it, what I had planned to do as my start, I did not do it finally, I could not do it. I was watching the energy that had already been created on stage by somebody, so I had to pick it up from there for my own self. I thought it was the best way to calm myself and energise myself at the same time - just draw from what the other person has left for you. Of course, once the music starts, everything is a blank, and that's the way I think it should be.

When my three and four were on, there was a lot of response. I could feel for myself that as I approached five, seven and then, nine, everybody started becoming quieter. I think that is what my focus in my mind was - to try to instill that silence which the classical art forms have. There is no formula for it, and that is the one thing I have taken away from this production.

HEMANT KALITA

|

| Hemant Kalita |

It was not just a performance for me. It was like a dip in the ocean. I had a lot of questions about the process. The performance had two stages - one inside and the other outside. Whenever I pray in front of a mirror, I say 'tumko mujhko naman naman'. One Hemant is inside and the other is outside. The artist outside says naman to the Hemant inside and that gelled with Kamalini Dutt's image. In the lines 'abhinav nartan kar raha', I asked why the use of the word 'nartan', and Kamaliniji told me, 'Tumhare andar nritya karta hai tabhi ang chalte hai' (The limbs move in dance because He dances within you). I thought I had been dancing for myself, for money and recognition, but this was an awakening. I have learnt a lot from the other dancers in the production. I feel more alive.

MANOHAR BALATCHANDIRANE

Mridangist Manohar Balatchandirane set the percussion for the Bharatanatyam pieces in the production. A disciple of Kumbakonam N. Padmanaban, he has accompanied various artists across India and abroad both in music and dance performances. Also a singer trained in Carnatic music, Manohar has knowledge of both Hindustani and Carnatic traditions. He describes how his mandala, a visual representation of the percussion in Rango'ntaratma, came about.

|

| Manohar Balatchandirane |

Further, what I did was to make the mandala into a meru, which is the 3-D projection of the mandala. This was very difficult to do with graphics and computers, though it might seem easy to visualize. I took care that each figure was repeated 15 times, which was the taala meter of the performance. The colours used are the traditional red and white. Kamaliniji also gave me the idea that everything emanates from the mandala, so the core should be a darker colour since everything originates from darkness, and then it should proceed outward to a lighter, more auspicious colour like yellow. The entire gradient ten would be like black to dark maroon to red to yellow.

Giving shapes to the talas

When we come to 'jham' which is the 'sam', we ascribe to it the most complete shape, the circle. The phrase jham ta jham ta taa: jham ta is a triangle, jham again is a circle and the long taa since it is twice as long as the ta, is a bigger triangle. Coming to the phrase ta ka taa ki ta, it is represented by 5 matras, so I have used 3 pentagons and then 3 septagons and 3 nanogons. This is repeated in equal geometry 15 times and it becomes a circle. I transposed this into a 3-D image rising from a 2-D image. It then becomes a mandala. This was a spiritual experience since I never knew that rhythm could be used in a visual form. Since I am a percussionist, it was a great mind exercise from me.

Music is both an oral and aural form traditionally. We in India do not have a visual tradition while in the west, it is a very well-defined codified form of defining rhythm with the help of bar graphs and lines. It works very well for them, but for us, since it is an oral tradition, much of it is lost in translation. We don't get to see what rhythm would look like when we see it from the visual perspective. It is just like a painter who is drawing what s/he infers from the dance. It should be done for rhythm as well. It is just like asking a painter to draw what s/he is inspired to do while Zakir Hussain is performing. It is very easy to move people with the melody but difficult to move them with the rhythm. But a visual representation will definitely help people perceive the rhythm. It took me many nights to complete this interaction and its transcription, and each night, it was like my inner ranga too danced the cosmic dance of naad and bindu when listening to the music.

Pics: Anoop Arora

Video courtesy Manohar Balatchandirane

Note: This article first appeared in narthaki.com

Comments

Post a Comment