Divya Goswami on Nādānt: Even if people understand 10 per cent, it's okay

|

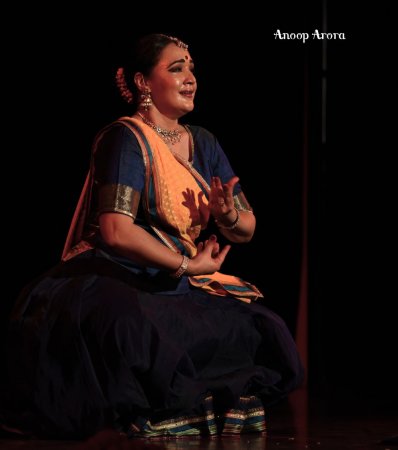

| Divya Goswami |

Divya Goswami is a well-known Kathak soloist whom I have watched and

admired for many years. She brings a rare intelligence and depth to

Kathak and the breadth of her influences is obvious in her productions.

Last year, I watched an excerpt from her production Nādānt, which she

premiered in Bengaluru in March 2024 in its full length of 75-80

minutes.

The press note about Nādānt describes it thus: 'There is a force of

existence, which cannot be contained by space or bound by time, yet it

is the one that creates the many dimensions, patterns and emotions. This

is the perpetual dance of existence, Nādānt, without a beginning or an

end, and at the very centre is Lord Shiva. Nādānt is an exploration by

Divya Goswami navigating through the leela of the manifest form of the

cosmic dancer and the visual discourse on the true purpose of existence;

until there is no more.'

Abstract as that is, Divya used her sensitive yet formidable technique

and the abstraction friendly form of Kathak to successfully convey that.

In my report on her performance in Delhi, I have written that 'Nādānt

(Naadaant) is the continuous cycle of creation and destruction, sound

and silence, pause and flow, at the centre of which is the lord himself

as a circle of fire. He dances and enjoys the dance of bliss in the hall

of consciousness.' Her dancing had 'soul', as always, and connected

effectively with the audience. The first section used a dhrupad composed

by Pandit Jasraj in raag Desh in a cycle of twelve beats. It depicted

Shiva as the param yogi, full of love and compassion and yet detached

from worldly pleasures. The second major section used Swathi Thirunal's

"Shankara Srigiri" to show the seeker wishing that the lord dance in the

lotus of her or his heart to burn away the fire of desires and the pain

of the worldly bindings.

I later did a full interview with Divya about how she turned an abstract

concept into a Kathak production and how even the nritta she chose was

intended to convey the concept rather than used simply as a connector to

display her technical prowess. She also discussed how, or how much, she

hopes to convey to audiences a concept so dense with transcendent

philosophy.

Thought process and choreographic choices

Divya spoke about the thought behind the production and the process of

deciding what kind of movement or choreography she would use to depict

it. She explained that, paradoxically for a concept that was so

philosophical, the starting point was simply a lot of dancing to prepare

the dancer's body for the depiction.

"We keep talking about formlessness, timelessness, nothingness. Whenever

I think about these philosophies, which we say are inherent in the

Indian arts, particularly in dance, the only image that comes to my mind

is Shiva. I do associate these things with Krishna as well, but if I

had to bring out a form for these philosophies, it would be Shiva.

I wanted to explore this idea and how I have gone about it is this:

usually in dance, we begin with building on the philosophy. We begin

with the form and then we ideate - we come up with metaphors, then

include the philosophy and then we say we have reached nothingness.

But whenever I have spoken to anybody, Guruji (Guru Munna Shukla) or

Amma (Kamalini Dutt) or any senior person I have had the chance to

interact with, whether it was my intensive with Akram Khan or anything

else - I have always realized that everybody says, before you come to

create a new work, you should have danced your body out. First prepare

your vessel, dance it all out; that will give rise to some philosophy,

after which you will experience nothingness, after which maybe in your

dance you feel one with the higher energy or calling.

That is exactly the thought I have gone with. I actually begin the

concert with a tarana, not a shloka or dhrupad, by preparing the body.

Once my body is tuned as an instrument, then I see my philosophy in the

form of Shiva, whatever it be - metaphors like the snakes or bhasma.

These are the two key points I have highlighted (and not extended the

depiction to other symbols and metaphors) because if you want to, you

can do so much in a dhrupad that there would be no scope of including

any other composition.

One dhrupad is sufficient to show all the metaphors and the higher

calling you want to suggest. But this dhrupad looks at Shiva in a very

different way. It says that he has all these things (snakes and bhasma

etc.), but he is very compassionate. He has all these things, but I feel

like loving him rather than being in awe of him or seeing him as a

mysterious figure. So I chose to delve into just two or three of his

metaphors through the dhrupad, not more, because it was becoming

unnecessarily heavy for me to convey and maybe too much for the audience

to take in as well.

And from that philosophical point of view, when Shiva has danced and

narrated why he has the snake and what he is doing with the bhasma,

whether it's the end product - bhasma cannot be further destroyed, which

is why it's so pious - once he's scattered it all around, once he's

danced on that cremation ground and prepared himself like that, then the

human is ready to enter into Shiva's arena and begins to see or

visualize his form. Then the human understands - this bhasma, I

understand what its meaning is for me, that I must destroy my ego to the

tiniest part possible. Or if I see a snake, I know that these represent

my vices and I accept them, because only if I accept them can I get rid

of them.

Here begins the "Shankara Srigiri", where the bhakta begins to enjoy the

dance with Shiva and communicates with him - you've prepared his

cremation ground, I see you, but how do I unite with you? Slowly Shiva

tells him, give me your snake, now I will apply the bhasma on you, now I

will throw the holy waters on you to cleanse you, and then the bhakta

eventually becomes one with the lord. This is the route I have taken,

rather than worshipping Shiva and his many features and ornaments and

then going the philosophical route. I have kept the philosophy at the

start because I have narrated it as the voice of Shiva.

"Shankara Srigiri" is the second major section and is a composition of

Maharaja Swathi Thirunal. It can't even be called the second piece - the

complete production is in four fragments. The first is the tarana,

which I didn't do in Delhi because time didn't permit; I started

directly with the dhrupad. After the dhrupad, the philosophy is danced

and Shiva says, now come and dance with me, I've prepared everything for

you, the stage is set. The bhakta enters by visualizing the form of

Shiva and for that point, I requested Himanshu Shrivastava, (artist,

scholar and Bharatanatyam dancer) to write a kavit (poem) for me. In

that way, I narrated the meanings I wanted to convey.

Himanshu made it into a very long poem, but I did not again want to

touch upon too many aspects of Shiva. I still wanted to stick with the

ghungroo or ashes, because if Shiva has prepared the arena through a

certain thought process, I have to be able to see it through that same

process. So then I wrote a paragraph about what I wanted to describe,

which Himanshu has kindly given me as a kavit.

So from visualizing the form as a bhakta, it moves into "Shankara

Srigiri". All these vices, the shad dosha (six doshas) within us, the

restlessness of the mind which is like the deer Shiva holds, or the

darkness of the cloud which Shiva can dissipate through the shower of

bliss - all these little metaphors, in tiny ways, I have tried to

incorporate in "Shankara Srigiri", eventually leading to the oneness of

the two. The knots inside all of us are opened by Shiva one by one until

the final lotus blooms above the sahasrara and that's where we hope the

union between the lord and the devotee will take place; we hope that

there will be no difference between them.

I later realized where this process came from (Here, Divya did not want

to convey the specifics of the incident because it involved a sensitive

element, so this has been paraphrased). I happened to inadvertently

offend someone during a convention once. I later went to apologize to

them when I realized that I had caused offence. In the course of my

apology, I said, 'God is everywhere.' But the person replied, 'What

nonsense! God is not where you're dancing (on the stage), tum to sirf

naach rahi ho (you are just performing).' We always say God is

everywhere, so this particular composition, when it says "Shankara

srigiri naath prabhu ke nritya virajat

chitra sabha mein" - the devotee has written it saying he is

residing in the sabha decorated with paintings. I have interpreted it

to mean that I have decorated my heart with the many paintings of

goodness, badness, darkness, evil, everything. Why don't you come and

reside within me? Because finally, it is my heart I am carrying

everywhere. It's immaterial whether I go to a temple or not. What really

is important is that we carry the awareness of you, that consciousness

and positivity in us. So you can create that chitra sabha anywhere if

you keep your heart pure.

This incident somehow just came to my mind while composing "Shankara

Srigiri" and I approached it from the start like that. I never once in

my whole composition dance the typical way of showing the temple and

what part of the temple he is residing in - I have not done any of that.

Right from the start, I have said, my heart, my body is the temple, you

come and reside in it because this is all I can carry, this is all I

have. All else is external and that is how it took a philosophical turn

rather than just being a dance. Strange how some incidents connect to

something else!"

Not repeating stances for snakes, bhasma etc.

Divya stuck to just the snakes and bhasma as the metaphors or symbols of

Shiva, but she did not repeat any stance to show them. The multitude of

stances she took at first seemed simply a display of her mastery of her

form. But Divya explained how that choice was also linked to the

philosophy of the concept.

"That was a conscious effort again. We say there are six doshas - kama,

krodha, mada, moha, lobha, matsarya. Each of them resides in different

parts in our body. If you consider this philosophically, especially in

Kashmir Shaivism and in others as well, they all speak about it - even

in healing, the tantric aspects of Shiva, it is mentioned that let's say

there is pain in your right hand. In tantric literature, Ayurveda and

many other places, it's mentioned that if it is some particular point in

your hand, that points to the root cause and the root cause is not a

disease, it is probably because you are jealous or stressed etc.

So I tried to take a leaf out of this, which is why I consciously showed

the main parts of the body when taking stances for the snakes. Like if

it was the ankle, then I know the simple thing to associate it with is

'I can't walk'. I can't take the step towards the lord. From there, I

started thinking, if this is one thing, then what else can there be? So

one was, if it is in my head or in my ear, then it is blocking my

ability to hear. So I tried to connect all those things and tried my

best to show that the vices or snakes can be anywhere, not just as they

are on the very famous Nataraja murti - one snake in the neck and one on

the hand and that's it. If you're associating the snake with evil or

vice or darkness in us, then it can be anywhere in us. That is why I

tried to show it in as many ways in my body as possible, though I am yet

to explore many more!"

How much of the thought and philosophy might the audience comprehend?

I asked Divya how much she thinks the audience might understand of the

concept. She said that even if they don't comprehend all of the

intellectual, philosophy-dense thought, she would be happy if they got a

'feel' of the sentiment she wanted to convey:

"As it is we don't explain things word by word - I am not explaining

every metaphor and pose. That is not even possible unless it is a

lec-dem and I have three hours. Then I can take you through why this

pose and what is my thought process and how it's connected to the next

one. But in a performance, there is no time for something like that.

Again, this is something I have discussed a great deal and I have had

the privilege of speaking to a few people of late on this topic. Even as

a spectator - I go for any performance, I don't restrict myself to just

Kathak; it's good art I really want to go and see - I feel every time

that I go watch dance, even if it's the same composition and a different

person is dancing, I don't understand everything. Even as a dancer I

don't understand everything. Even if it is Kathak, I might miss

something, even though the vocabulary is better known to me than that

of, say, Kuchipudi or Bharatanatyam. It always raises the question that

if I am not able to understand, as a practitioner of the art, how much

is the audience understanding? The audience in which there are maybe

practitioners, maybe lovers of art and maybe just random spectators come

to view something for the first time.

What I have understood after speaking to a few people about this is that

firstly, I don't think it is right of me to assume that the audience

doesn't already know the stories or literature on which the production

is based. At some level or the other, I feel if I am convinced and true

to what I wish to convey, some kind of vibration will be felt by the

audience. That is what we hope for, that is the end product of the

performance - ras utpatti (the creation of rasa). In my performance,

even if somebody feels that oh wow, Shiva is dancing with so much

vigour, even if they feel just that much, or that the end was high on

energy or the silence was so strong - I think that's enough. I really

can't expect people to understand every single thing when they're

watching it only once and I have been working on it for three years. It

is just not possible. So I am actually very grateful that I always get

mixed opinions.

You are asking me questions so I am thinking about it. Somebody else

might say that 'I haven't understood any of what you have done'. It

pushes me to think that maybe the thought process was in my head but

maybe the delivery was not good enough or clear enough. So I go back and

work on it to try and make it even simpler. Sometimes we think everyone

knows these things but then we find oh, even this is not known to

everyone! That is why I love to speak to all kinds of people at the end

of the performance and even if someone can tell me one small thing which

they felt I could improve, then maybe next time, rather than

understanding 10 per cent, people will understand 15 per cent. This is

something that I think I am very accepting of, that I am taking such a

huge philosophical POV with my production. And it is not just praising

Shiva and showing a hundred poses of Shiva and it'll not be that dynamic

quality that Kathak has. That is something I am mindful of and that is

deliberate on my part. In that, even if people understand 10 per cent -

100 is too much to expect - it's okay."

The breadth of movement in 'Shankara Srigiri'

In "Shankara Srigiri", Divya's movement was expansive, covering the

whole stage from one side to the other. Again, she said that was a

concept-led choreographic choice.

"That was the whole idea - that there is a stillness in Shiva which a

restless bhakta wants and is trying to achieve, how will I show that

restlessness. The only way we have is our vocabulary of Kathak, which is

perfect because Kathak has so much movement. So I used the Kathak bols

there to show that restless energy. Shiva is everywhere, but the bhakta

just wants some way of connecting with him. And see, I didn't have to

tell it to you, but you understood. It ends with the depiction that the

bhakta sees himself in Shiva and Shiva comes into him as well - both

ways."

The colour of the costume in the Delhi performance, the blue of the Neelkanth that Divya wore, was also a deliberate choice.

Pics: Anoop Arora

Note: This article first appeared in narthaki.com

Comments

Post a Comment